News & Features

Mediation Retreat at Toggenburg, Switzerland.

Talk on Meditation and Ancient Eastern Wisdom for Modern Life at EPFL

Meditation workshop at EPFL University in Switzerland

7-Day Vipassana Retreat – Every Month at Rideekanda Forest Monastery

🌿 7-Day Vipassana Retreat – Every Month at Rideekanda Forest Monastery 🌿

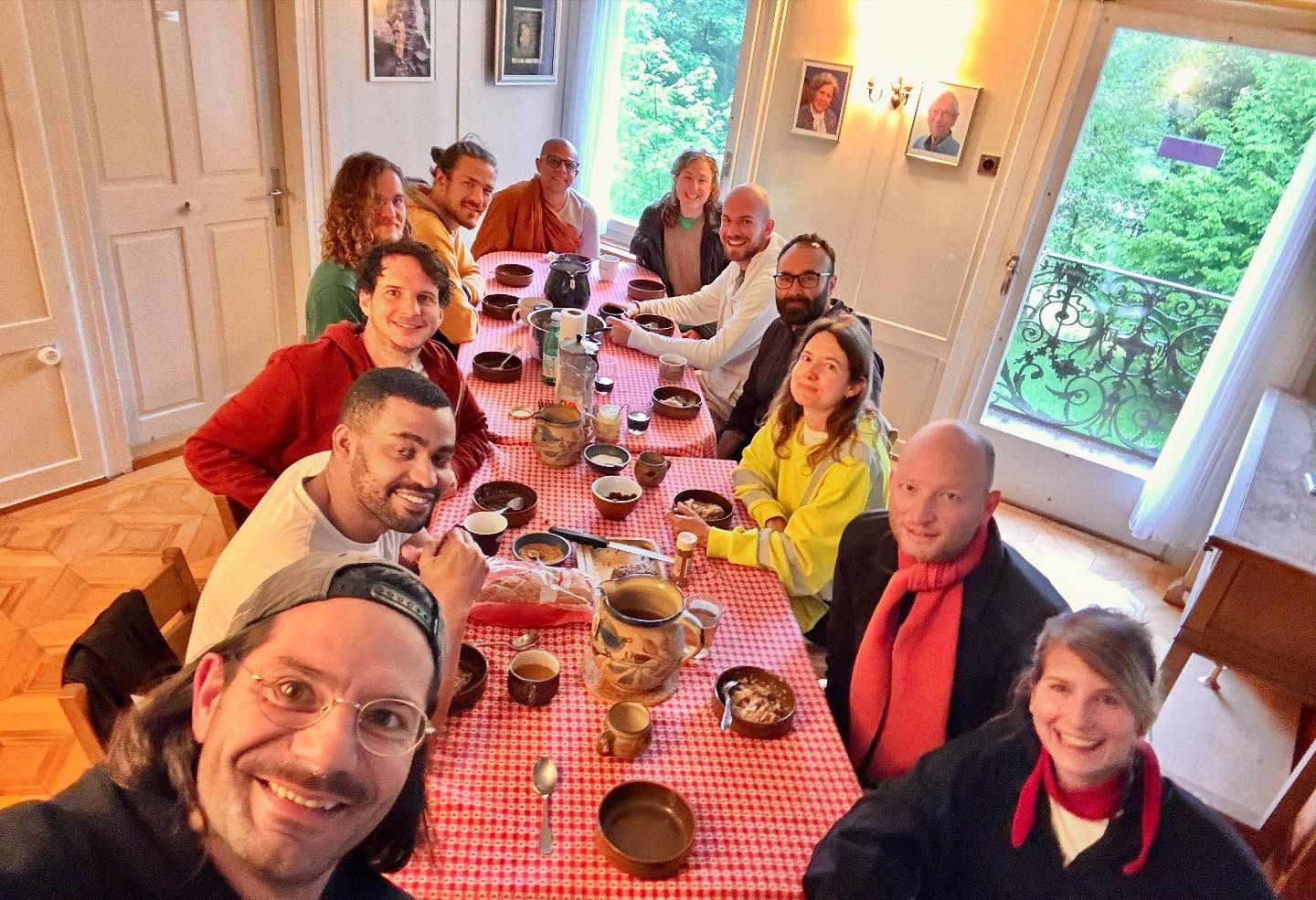

In August, we welcomed another group of dedicated practitioners—both local and international—for our 7-day Vipassana retreat at Rideekanda Forest Monastery.

Each month, we open the doors of our serene mountain-top monastery in Matale for a week of mindful silence, meditation, and guidance rooted in the authentic teachings of Theravāda Buddhism.

✨ About the Retreat

-

Vipassana Practice – A systematic training in insight meditation, guided by experienced monastic teachers.

-

Daily Schedule – Structured days of meditation, chanting, and Dhamma discussions, balanced with personal reflection.

-

Supportive Environment – A sacred forest monastery setting, away from distractions, where both beginners and seasoned practitioners can deepen their practice.

-

Community of Seekers – Each retreat brings together participants from Sri Lanka and across the world, creating a shared journey of stillness and discovery.

🙏 Why Join?

This retreat is an opportunity to step away from the busyness of daily life, reconnect with yourself, and cultivate clarity, compassion, and inner peace.

📅 Upcoming Retreats

Our 7-day Vipassana retreats are conducted every month. Spaces are limited, so early booking is encouraged.

📞 For inquiries & reservations:

WhatsApp: +94 74 225 2980

Email: rideekanda@gmail.com

✨ Rideekanda Forest Monastery – where silence speaks and the path to liberation unfolds. ✨

Residential Retreat

Here’s a refined draft you can use for a web post about the Rideekanda Forest Monastery Residential Retreats, weaving together the guidelines, program details, and atmosphere reflected in your documents and photos:

🌿 Residential Retreats at Rideekanda Forest Monastery 🌿

Nestled in the tranquil forests of Matale, Sri Lanka, Rideekanda Forest Monastery offers a rare opportunity to step away from the distractions of modern life and immerse yourself in a journey of mindfulness, simplicity, and inner peace.

Our Residential Retreats are designed for those seeking to deepen their meditation practice and experience the transformative teachings of Theravāda Buddhism in a serene natural setting.

✨ What to Expect

-

Mindful Living – Simple accommodations free of modern distractions, fostering focus and stillness.

-

Daily Practice – A structured rhythm of guided meditation, walking meditation, Dhamma discussions, and chanting.

-

Wholesome Meals – Nutritious vegetarian food prepared with care to support your practice.

-

Nature & Silence – A sacred environment where silence, respect, and mindfulness create harmony with the forest surroundings.

👥 For Whom?

Our retreats welcome monks, nuns, and lay practitioners alike, regardless of experience level. Whether you are beginning your meditation journey or deepening your existing practice, you will find supportive guidance here.

🌸 Retreat Highlights

-

Personalized meditation guidance from experienced instructors led by Ven.Homagama Rewatha Thero.

-

Opportunities to practice Samatha and Vipassana meditation systematically.

-

A chance to reconnect with nature while cultivating inner clarity and compassion.

-

A peaceful retreat environment supported entirely by generosity and donations.

📍 Location

The monastery is located atop a serene mountain in Yatawatta, Matale, surrounded by pristine forest, accessible by public or private transport with final transfers arranged by the monastery.

🙏 How to Join

Retreats are offered in varying lengths—from short weekend stays to month-long immersions. As spaces are limited, advance booking is required.

📞 Contact us via:

WhatsApp: +94 74 225 2980

Email: rideekanda@gmail.com

✨ Step into the stillness. Rediscover yourself. Journey towards peace. ✨

Introduction to Meditation with Banthe Rewatha in Johanneskirche, Zürich, Switzerland

Vipassana Meditation Retreat with Banthe Homagama Rewatha in Toggenburg Switzerland

Wisdom in Silence

07 days Vipassana Retreats @ Rideekanda

Sucessfully completed the retreats for foreigners and locals meditaiton practitioners @ Rideekanda Forest Monastery, Udasgiriya, Matale, Sri Lanka.

“Bound by Peace, Guided by Silence”

Celebrating the completion of meditation retreats

Celebrating a Sacred Tradition: The Temporary Ordination of a Foreign Monk at Rideekanda Forest Monastery

Celebrating a Sacred Tradition: The Temporary Ordination of a Foreign Monk at Rideekanda Forest Monastery

Greetings to our beloved community,

We are filled with joy and spiritual warmth as we share the news of a remarkable event that recently graced the sacred grounds of Rideekanda Forest Monastery. In a beautiful ceremony steeped in ancient tradition, we welcomed a foreign monk into our spiritual family through a temporary ordination.

The ordination ceremony was a profound expression of cultural and spiritual unity, bridging distant lands through the universal language of faith. It was an honor to witness the dedication of our new brother, who has traveled far to seek wisdom and peace in the serene embrace of our monastery.

This special event began with the chanting of sutras, resonating through the lush greenery of our forest surroundings. The air was filled with the scent of incense and the serene sounds of traditional instruments, creating an atmosphere of deep reverence and tranquility.

Our esteemed elders led the ordination, bestowing the saffron robes upon our new monk in a symbolic gesture of renunciation and commitment to the monastic life. The community gathered in support, offering blessings and prayers as he embarked on this sacred journey.

This temporary ordination is not just a personal milestone for the monk but a celebration of the diversity and inclusivity that are core to our beliefs. It reminds us that the path to enlightenment transcends geographical boundaries and cultural differences.

We invite you to reflect on the beauty of this event and the lessons it brings to our lives. May this ordination inspire us all to embrace our spiritual journey with renewed vigor and an open heart.

In peace and solidarity,

[Rideekanda Forest Monastery Team]

බිත්තරයෙන් මතුවන යථාර්ථය!

Foreigners' Retreat @ Rideekanda Forest Monastery | Meditation Retreat

The "Foreigners' Retreat" video focuses on the residential retreats offered at the Rideekanda Forest Monastery, which provides accommodation for both male and female meditation practitioners, including Buddhist monks and nuns. The retreat programs are flexible and tailored to meet the individual objectives and requirements of the participants. There are no fixed dates for the retreats, and participants can plan their stay based on their own schedule. The aim of the residential programs is to help participants reach the highest understanding of Theravada Buddhism – Nibbana. The training methodology includes the systematic teaching of Tripitaka, analysis of dhamma and discipline, and personalized meditation recommendations. The retreat also offers one-to-one communication with instructors.

තාවකාලික පැවදි පුහුණු වැඩසටහන | රිදීකන්ද ආරණ්යය | Temporary Ordination Documentary

බෝධි පූජාවේ යථාර්තය

වෙසක් මාසයේ සම්බුදු තෙමඟුල අර්ථාන්විතව සමරන්න අදහසක්

පොහොය දිනයේ සිල් සමාදන් වීමේ වැදගත්කම

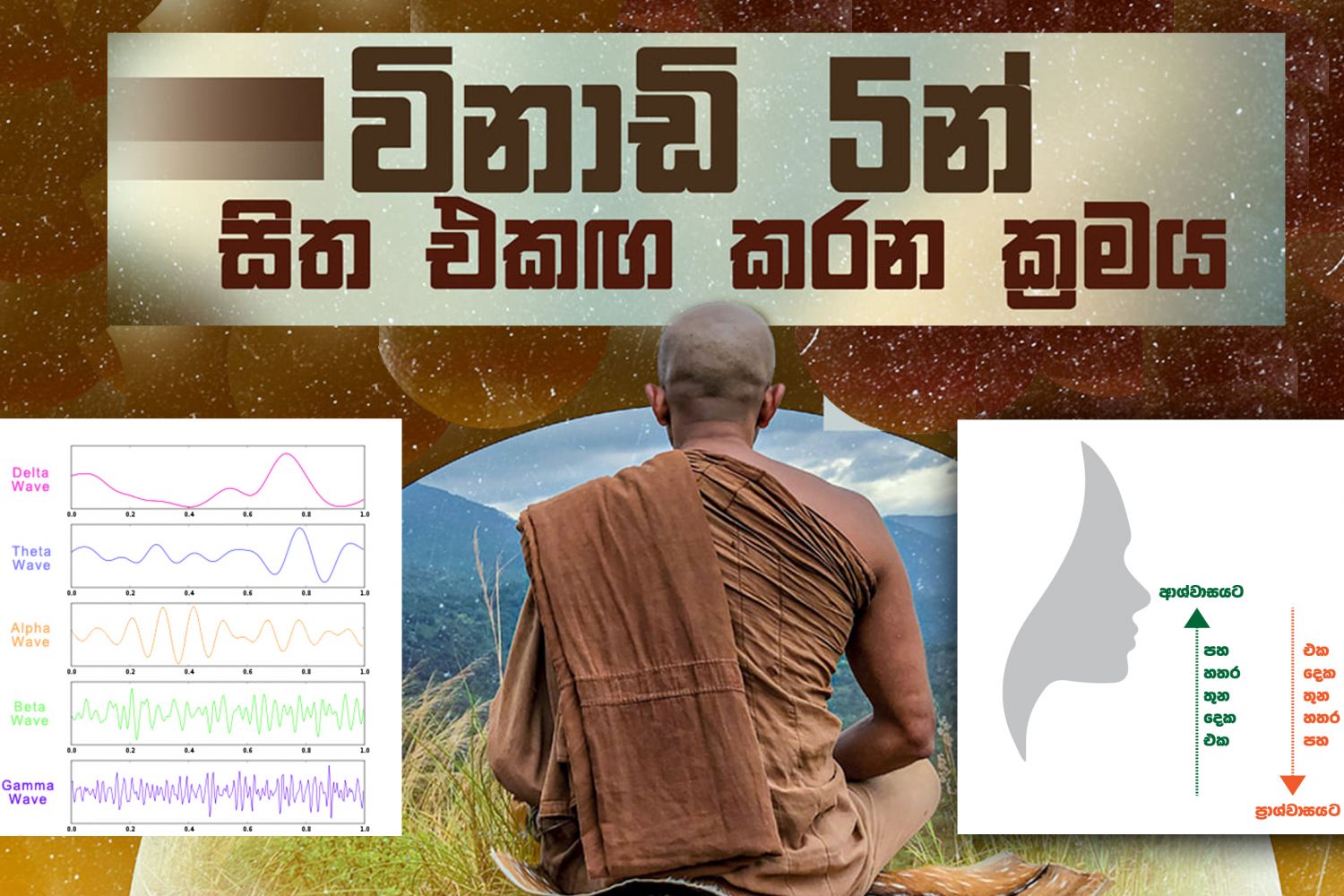

විනාඩි 5 න් සිත එකඟ කරන ක්රමය

ආර්ය මාර්ගයේ පළමු පියවර

භාවනාව සහ විවිධ භාවනා ක්රම

Monsoon Season at Rideekanda Forest Monastery

Monsoon Season starting from the month of October to December in Matale, Sri Lanka brings a more meditation-friendly environment that creates suitable cold weather, monotonous rainy sounds, and feasible light conditions. It helps to enhance the mood and capacity of meditation practitioners to carry out their practices effortlessly. Gloominess, mist, and the dew light bring more freshness and a relaxed mind that helps in healing both body and mind functions. Monotonous rainy sounds trigger the alpha brain wave functions, which helps in tranquilizing the mind.

Almsgiving and Opening Ceremony of Accommodation Building

පඬු චීවර සැකසීම

Chevarara, which is created in parallel to the Katina Ceremony, is made in the form of ancient Theravada practice by Buddhist monks in ancient times. Natural herbs such as plants leaves, roots, nuts and flowers are used to make the Pandu (a blend) which makes the colour similar to the natural acrid mixture. This process is done by the meditation practitioners through a form of meditation. In order to make this special blend called Pandu to a correct proportion, they have to commit approximately two months and a 24×7 continuous process with close supervision.

In parallel to the above process, the stitching of Cheevaraya (robe) is done in another place. For that unprocessed white clothes are used. The Cheevaraya (robes) is prepared by sewing pieces of cloth together and placed the pieces similar to the layout of the paddy field. The Cheevaraya (robes) of the early monks were made of scraps of discarded cloth from cemeteries.

After successfully making the blend and stitching of Cheewaraya, the next process is to paint the cheevaraya using the blend. A wooden canoe is used for the panting process and this process is repeated until the correct colour of the Cheevaraya is made.

Making of Pathra

Every day Buddhist Monks, young and old make their early morning alms collection called Pindapathaya , mostly of prepared food that they eat when they return to the temple. People look out for the monks from their homes, markets or certain places where they know monks usually pass to make their offerings. They put food in the Pathra (bowls) that the monks carry, the monks then chants a blessing before moving on. The practice of giving plays an important part in developing spirituality among Buddhist people and the alms bowl is very symbolic of this.

Pathraya is a most important part of the Buddhist Monks where, the ancient days monks were used clay and steel Pathra. The natural black lacquer finish is to be made on the surface of the Pathraya before use. This black lacquer finish is made by using natural sesame oil.

Use of sesame oil to make the black lacquer on the Pathraya, is acting as a germicidal environment when eating food as well as the natural black color is more convenient when monks who are living in forest.

Bodhi-Puja

The veneration of the Bodhi-tree (pipal tree: ficus religiosa) has been a popular and a widespread ritual in Sri Lanka from the time a sapling of the original Bodhi-tree at Buddhagaya (under which the Buddha attained Enlightenment) was brought from India by the Theri Sanghamitta and planted at Anuradhapura during the reign of King Devanampiya Tissa in the third century B.C. Since then a Bodhi-tree has become a necessary feature of every Buddhist temple in the island.

The ritualistic worship of trees as abodes of tree deities (rukkha-devata) was widely prevalent in ancient India even before the advent of Buddhism. This is exemplified by the well-known case of Sujata’s offering of milk-rice to the Bodhisatta, who was seated under a banyan tree on the eve of his Enlightenment, in the belief that he was the deity living in that tree. By making offerings to these deities inhabiting trees the devotees expect various forms of help from them. The practice was prevalent in pre-Buddhist Sri Lanka as well.

According to the Mahavamsa, King Pandukabhaya (4th century B.C.) fixed a banyan tree near the western gate of Anuradhapura as the abode of Vessavana, the god of wealth and the regent of the North as well as the king of the yakkhas. The same king set apart a palmyra palm as the abode of vyadha-deva, the god of the hunt (Mhv. x,89, 90).

After the introduction of the Bodhi-tree, this cult took a new turn. While the old practice was not totally abandoned, pride of place was accorded to the worship of the pipal tree, which had become sacred to the Buddhists as the tree under which Gotama Buddha attained Enlightenment. Thus there is a difference between the worship of the Bodhi-tree and that of other trees.

To the Buddhists, the Bodhi-tree became a sacred object belonging to the paribhogika group of the threefold division of sacred monuments, while the ordinary veneration of trees, which also exists side-by-side with the former in Sri Lanka, is based on the belief already mentioned, i.e. that there are spirits inhabiting these trees and that they can help people in exchange for offerings.

The Buddhists also have come to believe that powerful Buddhist deities inhabit even the Bodhi-trees that receive worship in the purely Buddhist sense. Hence it becomes clear that the reverence shown to a tree is not addressed to the tree itself. However, it also has to be noted that the Bodhi-tree received veneration in India even before it assumed this Buddhist significance; this practice must have been based on the general principle of tree worship mentioned above.

Once the tree assumed Buddhist significance its sanctity became particularized, while the deities inhabiting it also became associated with Buddhism in some form. At the same time, the tree became a symbol representing the Buddha as well. This symbolism was confirmed by the Buddha himself when he recommended the planting of the Ananda Bodhi-tree at Jetavana for worship and offerings during his absence (see J.iv,228f.). Further, the place where the Buddha attained Enlightenment is mentioned by the Buddha as one of the four places of pilgrimage that should cause serene joy in the minds of the faithful (D.ii,140). As Ananda Coomaraswamy points out, every Buddhist temple and monastery in India once had its Bodhi-tree and flower altar as is now the case in Sri Lanka.

King Devanampiya Tissa, the first Buddhist king of Sri Lanka, is said to have bestowed the whole country upon the Bodhi-tree and held a magnificent festival after planting it with great ceremony. The entire country was decorated for the occasion. The Mahavamsa refers to similar ceremonies held by his successors as well. It is said that the rulers of Sri Lanka performed ceremonies in the tree’s honour in every twelfth year of their reign (Mhv. xxxviii,57).

King Dutugemunu (2nd century B.C.) performed such a ceremony at a cost of 100,000 pieces of money (Mhv. xxviii,1). King Bhatika Abhaya (1st century A.C.) held a ceremony of watering the sacred tree, which seems to have been one of many such special pujas. Other kings too, according to the Mahavamsa, expressed their devotion to the Bodhi-tree in various ways (see e.g. Mhv. xxxv,30; xxxvi, 25, 52, 126).

It is recorded that forty Bodhi-saplings that grew from the seeds of the original Bodhi-tree at Anuradhapura were planted at various places in the island during the time of Devanampiya Tissa himself. The local Buddhists saw to it that every monastery in the island had its own Bodhi-tree, and today the tree has become a familiar sight, all derived, most probably, from the original tree at Anuradhapura through seeds. However, it may be added here that the notion that all the Bodhi-trees in the island are derived from the original tree is only an assumption. The existence of the tree prior to its introduction by the Theri Sanghamitta cannot be proved or disproved.

The ceremony of worshipping this sacred tree, first begun by King Devanampiya Tissa and followed by his successors with unflagging interest, has continued up to the present day. The ceremony is still as popular and meaningful as at the beginning. It is natural that this should be so, for the veneration of the tree fulfils the emotional and devotional needs of the pious heart in the same way as does the veneration of the Buddha-image and, to a lesser extent, of the dagaba.Moreover, its association with deities dedicated to the cause of Buddhism, who can also aid pious worshippers in their mundane affairs, contributes to the popularity and vitality of Bodhi-worship.

The main centre of devotion in Sri Lanka today is, of course, the ancient tree at Anuradhapura, which, in addition to its religious significance, has an historical importance as well. As the oldest historical tree in the world, it has survived for over 2,200 years, even when the city of Anuradhapura was devastated by foreign enemies. Today it is one of the most sacred and popular places of pilgrimage in the island. The tree itself is very well guarded, the most recent protection being a gold-plated railing around the base (ranvata).

Ordinarily, pilgrims are not allowed to go near the foot of the tree in the upper terrace. They have to worship and make their offerings on altars provided on the lower terrace so that no damage is done to the tree by the multitude that throng there. The place is closely guarded by those entrusted with its upkeep and protection, while the daily rituals of cleaning the place, watering the tree, making offerings, etc., are performed by bhikkhus and laymen entrusted with the work. The performance of these rituals is regarded as of great merit and they are performed on a lesser scale at other important Bodhi-trees in the island as well.

Thus this tree today receives worship and respect as a symbol of the Buddha himself, a tradition which, as stated earlier, could be traced back to the Ananda Bodhi-tree at Jetavana of the Buddha’s own time. The Vibhanga Commentary (p.349) says that the bhikkhu who enters the courtyard of the Bodhi-tree should venerate the tree, behaving with all humility as if he were in the presence of the Buddha. Thus one of the main items of the daily ritual at the Anuradhapura Bodhi-tree (and at many other places) is the offering of alms as if unto the Buddha himself. A special ritual held annually at the shrine of the Anuradhapura tree is the hanging of gold ornaments on the tree. Pious devotees offer valuables, money, and various other articles during the performance of this ritual.

Another popular ritual connected with the Bodhi-tree is the lighting of coconut-oil lamps as an offering (pahan-puja), especially to avert the evil influence of inauspicious planetary conjunctions. When a person passes through a troublesome period in life he may get his horoscope read by an astrologer in order to discover whether he is under bad planetary influences. If so, one of the recommendations would invariably be a bodhi-puja,one important item of which would be the lighting of a specific number of coconut-oil lamps around a Bodhi-tree in a temple. The other aspects of this ritual consist of the offering of flowers, milk-rice, fruits, betel, medicinal oils, camphor, and coins. These coins (designated panduru) are washed in saffron water and separated for offering in this manner.

The offering of coins as an act of merit-acquisition has assumed ritualistic significance with the Buddhists of the island. Every temple has a charity box (pin-pettiya) into which the devotees drop a few coins as a contribution for the maintenance of the monks and the monastery. Offerings at devalayas should inevitably be accompanied by such a gift. At many wayside shrines there is provision for the offering of panduru and travellers en route, in the hope of a safe and successful journey, rarely fail to make their contribution. While the coins are put into the charity box, all the other offerings would be arranged methodically on an altar near the tree and the appropriate stanzas that make the offering valid are recited. Another part of the ritual is the hanging of flags on the branches of the tree in the expectation of getting one’s wishes fulfilled.

Bathing the tree with scented water is also a necessary part of the ritual. So is the burning of incense, camphor, etc. Once all these offerings have been completed, the performers would circumambulate the tree once or thrice reciting an appropriate stanza. The commonest of such stanzas is as follows:

Yassa mule nisinno va

sabbari vijayam aka

patto sabbannutam Sattha

Vande tam bodhipadapam.

Ime ete mahabodhi

lokanathena pujita

ahampi te namassami

bodhi raja namatthu te.

“I worship this Bodhi-tree seated under which the Teacher attained omniscience by overcoming all enemical forces (both subjective and objective). I too worship this great Bodhi-tree which was honoured by the Leader of the World. My homage to thee, O King Bodhi.”

The ritual is concluded by the usual transference of merit to the deities that protect the Buddha’s Dispensation.

from “Buddhist Ceremonies and Rituals of Sri Lanka”

by A.G.S. Kariyawasam

The Wheel Publication No. 402/404

What if We can Become a Lotus?

Lotus flower and leaf have a self-cleaning property: when water droplets touch the surface of a lotus flower or leaf, they pick up all the dirty particles and roll off from the surface due to it’s micro and nanoscopic architecture.

Humans, as well as all beings, lack this self-cleaning quality – as a result they get polluted by input received from six senses: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind.

For example; even though input received by an eye is only a colour; humans, through their individual interpretations, offer widely different meanings to what they see. What is actually happening is when light rays that reflect off objects and travel through the eye’s optical system are refracted and focused on a point of sharp focus. When the brain takes two images from each eye, these are then combined with ‘individual interpretation’ of the object, which leads to ‘subjective perception’ of the object that differs from ‘objective reality’. As a result, each individual may, like, dislike or neither like nor dislike of what she/he sees.

Due to this subjective interpretation, humans always suffer or get tired due to the continuation of the thought process attached to this. As beings, we always receive 5 inputs such as color, sound, taste, aroma and feels (temperature or pressure), subjective interpretation of which makes people dirty always.

Hence, the Buddhist philosophy always encourages humans to become a “Lotus” because it makes people self-cleaning, which means that when an input is received from five senses, humans do not make subjective interpretations.

From an insightful perspective, we should understand ‘subjective interpretation’ as dirty particles in the lotus parable and when we let objective reality to occur (as Surface in the lotus parable), we see ‘reality’, and thus, we don’t get polluted.

In other words, the subjective judgments that have been made with five senses are like mirages or illusions because these reflect nothing useful or never will people get satisfied – deers being deceived by a mirage and running towards the mirage never being able to satisfy the thirst.

But what if someone can understand that the subjective interpretations of inputs are not real but only illusions and the decisions that are taken based on the illusions are falsified/invalid?

To understand this phenomenon better: think about a time when we see a dream; the dreamer is not aware that he is in a dream: he is experiencing a situation as real. But if he suddenly wakes up and thinks about the dream, he will realize that all the decisions that have taken on the dream are useless.

In summary, all beings suffer due to the acceptance of illusions/ subjective interpretation as real, the repercussion of which is to get polluted themself due to faulty decisions. Therefore, by understanding the world as full of illusions, and developing the ‘self-cleaning property’ (i.e. the skill to observe ‘objective reality’ rather than letting subjective interpretation takes over) he/she can definitely be a “Lotus”.

Reference: Sūtra on the White Lotus of the Sublime Dharma (In Sanskrit: Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra)

Author – Ven. Homagama Rewatha Thero

ආර්ය මාර්ගයේ පළමු පියවර

Analysis of the teaching of the Five Aggregates

TERMS OF REFERENCE

A brief introduction on the Buddhist doctrine and defining the meaning of “khanda” as per the texts.

Analysing the intention/concept of describing the “Five Aggregates” in the Buddhist doctrine.

Analysing the functions of the “Five Aggregates” concerning the whole creation of the world. – construction of aggregates- construction of a self

– construction of an external

– construction of a sensation

Analysing the manipulation of the “Five Aggregates” concerning the Nibbana. – manipulation through three characteristics

– manipulation through ten perceptions described in “girimananda sutta”.

Conclusion

INTRODUCTION

The Buddhist philosophy emerged as a solution when people were identifying the problem of suffering such as death, illness and ageing. the enlightenment is nothing but the knowledge of the entire creation and that maturity of everything is led to the end of suffering. To achieve the supreme knowledge of the entire creation of the world, the Buddhist philosophy creates a tool that helps to study the true mechanism of the world. It is referred to as “khanda” in Pāli language, in this article, it is referred to as “Five Aggregates”.The word “khanda” referred to as bundles or piles of form, feeling, perception, fabrications, and consciousness that functioning in an array to create one unique result called “clinging- khanda” (Pancha-uphādhānakhanda). The functions of “clinging-khanda” described the creation of the world that will lead to the suffering and the manipulation or deconstruction of five aggregates lead to the end of suffering.

FUNCTIONS OF THE FIVE AGGREGATES

Five Aggregates are derived from 7 universal mental factors (sabbacitta-sadharana-caitisika) described in Abhidhamma texts. They are the skeleton of creation of the world, functioning with their 52 unique characteristics and 7 are common to any creation, and for easy analysis, 5 characteristics are taken out to explore as “Five Aggregates” in terms of their functions. [Figure 1.0]

Five Aggregates are functioning as per the Links of Dependent Origination (Patichcha Samuppadaya). For example; causes and effects of one Aggregate will lead to the functioning of the next aggregate. This process will lead to the continuation of the life cycle. Continuation of the processes will lead to making things permanent, permanency caused to the creation of individuality, both above factors will create a feeling of aspiration and desires. Desires are always converted to endless suffering. [Reference: Dammachakka sutta]

PROCESSES OF FIVE AGGREGATES

Mainly there are two processes that can be identified. that can be named as vertical process and the horizontal process.

The vertical process has described the initial development of Five Aggregates and the looping function of the same.

The horizontal process has described the expansion of Five Aggregates within the fourth Aggregate called “fabrications” (sankāra). Further, it is described the diversity and the complexity of the world that has been created through Five Aggregates. [reference: khajjanēya sutta, pārileyyaka sutta, punnama sutta]

The vertical process

The causes and effects of initial development of Five Aggregates consists of five great existents called “Dhāthu” and unsatisfied desires that come from the previous loops of five aggregates called “Kamma-viññāṇa”.

Initial foaming of great existents (Dhāthu) and unsatisfied desires (Kamma-viññāṇa), is described as the 1st stage of the Five Aggregate called Form (rupa-khanda). the forming function will create a basic form of colour, sound, smell, taste, sensations such as temperature and pressure. the basic form of these above elements can be identified as energy forms.

These energy forms are then converted to the feeling stage described as the 2nd stage of the Five Aggregates. the Feeling (vedanā-khanda) referred to the very fine and tenuous feeling of the energy forms that have been formed previously.

The fine and tenuous feeling then develop to make a sense or perception by relating the present feeling with the past unsatisfied desires/experiences. This is the 3rd stage of Five Aggregates called Perception (sañña-khanda).

The fourth stage of the process has highlighted more in the Pali texts and it described how the world is projecting or fabricating through this process called Fabrication (saṅkhāra-khanda). This projection/fabrication is divided into three steps called; the sight (Ditti), the measurement (Māna) and the desire (Tanhā)

The sight (Ditti) can be described as the process of projection/ fabrication through colour, sound, smell, taste, sensation such as temperature and pressure. this projection will lead to create three- dimensional space and the individuality.

The comparison between the individuality and the outer projected space called the measurement (Māna). These measurements determine the time as past, present and future, the distances, roughness and smoothness etc.,

The result of the measurement will create the desires/lust. More the processes of measurement and the sight, proportionally the desire (Tanhā) will increase accordingly.

The result of these three steps of processes (Ditti), (Māna) and (Tanhā) can be defined as the creation of the whole world.

Even though these processes are described in detailed the actual speed of these processes are instantly fugitive (khana) or called as impermanence (anicca). This impermanency affected to the instability of what it’s fabricated or projected too. For example; the projection that developed at this point such as individuality, the outer physical space and the desires that developed through the measurements (can be defined as the whole world) will be vanished off with the timeless changed that has affected to this processes.

This dissolution will lead to creating the unsatisfied desires (Kamma) and that will be animated towards fabricating/projecting the world again, this process is known as the Consciousness (viññāṇa-khanda), the fifth stage of Five Aggregates.

The horizontal process

As described in the fourth stage, the Fabrication process is the most important section because the presence of the physical world is appeared here.

The physical world is consists of the individuality and outer space with whole objects and the sensations that feel within it. The world that fabricated/projected has many complexities and it is more diversified with emotions and feelings with pleasant, painful or neutral ranges.

To understand the concept of being a complex or diversified world, sub-processes of the Five Aggregates have described in the Pali contexts.

the forming (rupa-khanda) will be the contacting of sights, sound, smell, taste, touches and memories with the physical sensors.

The feeling (vedanā-khanda) refers to the pleasant, unpleasant and neutral (neither pleasant nor unpleasant) sensations that occur when our internal sense organs come into contact with external sense objects and the associated consciousness.

The perception (sañña-khanda) can be defined as grasping at the distinguishing features or characteristics. It is also said that sañña registers whether an object is recognised or not.

The fabrication (saṅkhāra-khanda) has been described as all types of mental habits, thoughts, ideas, opinions, prejudices, compulsions, and decisions triggered by an object.

The Consciousness (viññāṇa-khanda) refers to the drives that bring desires repeatedly.

By analysing both the processes, vertical process of Five Aggregates will lead to creating the individuality, the external and its desires. The horizontal process of Five Aggregates will expand the same to the endless possibilities of sensation and it will incorrectly confirm the world is truly existing which will lead to the endless suffering. [Figure 2.0]

MANIPULATION OF THE “FIVE AGGREGATES” IN RESPECT TO THE NIBBANA.

Manipulation through three characteristics such as Anicca (not stable), Dukkha (suffering) and Anatt(Not a self).

When studying the concept of Five Aggregates, it is understood five aggregates are instantly changing their positions from one to another, this instability called the “anicca”. if the process is impermanent the result which gains through this also be impermanence.

Because of the characteristics of impermanency, un-satisfaction is always their in the process of Five Aggregates, that we called the Dukkha (suffering)

If the result is not controllable due to impermanency, how would be the individuality existed?

Manipulation through ten perceptions described in “Girimananda sutta”

In the perception process of Five Aggregates, always present feeling will be compared with the past experiences/ past unsatisfied desires. All these experiences are rooted with an individuality, permanency and expecting a feeling of pleasure.

The concept of Girimananda Sutta is that to change the comparison to ten new perceptions described in the Sutta instead of the normal pattern. For example, if the present feeling compared with the conception of perception of inconstancy, it will lead to breaking the normal flow of the process of Five Aggregates.

Likewise, there are ten Perceptions as follows to filtered along with the 3rd stage of the process called Perception, in order to deconstruct the processes of Five Aggregates.

Perception of inconstancy, perception of not-self, perception of unattractiveness, perception of drawbacks, perception of abandoning, perception of dispassion, perception of cessation, perception of distaste for every world, perception of the undesirability of all fabrications and the mindfulness of in-&-out breathing. The tenth perception is nothing but the practical way of doing the filtration of all above.

CONCLUSION

Considering all the above analysis according to the Pali texts, it is well understood that the Five Aggregates are the main conceptual tool to understand processes of creation of the world and also to destruct the whole process that caused suffering.

Author:Ven.Homagama Rewatha Thero